In some places outside livestock production may not be viable in the future due to extreme heat stress, says new paper

A new paper* presents new information on projected increases in extreme heat stress in five of the major domesticated animal species (cattle, sheep, goats, poultry, and pigs) during the present century.

Current domesticated livestock niches will become hotter and wetter, and extreme heat stress will become more pervasive. By the 2050s, some locations will become too hot and humid for animals to thrive without considerable adaptation. In such areas, extensive animal production may no longer be possible.

Authors assembled projected climate data for current and future time slices (years 2000, 2050 and 2090) in response to a lower and a higher greenhouse gas emission scenario to simulate feasible future climatic conditions.

Some 8% of the global cattle herd is currently located in areas with 8 days per year of extreme heat stress in 2000. The number of days per year of extreme heat stress increases to 19 and 24 in 2050 under the two scenarios (SSP1-2.6 and SSP5-8.5), respectively. By 2090, the percentage of cattle affected has declined slightly under one of the scenarios (SSP1-2.6). This is because this scenario envisages that greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions will peak in 2060. Under the other scenario (SSP5-8.5), by 2090, more than 60% of the global cattle herd is projected to experience nearly 70 days per year of extreme heat stress. This is because this scenario represents a very high GHG-emission future. Acclimation and adaptation can occur within and between generations, but unabated extreme heat stress may severely affect the animal's reproductive cycle, reduce feed intake and production, and eventually lead to death.

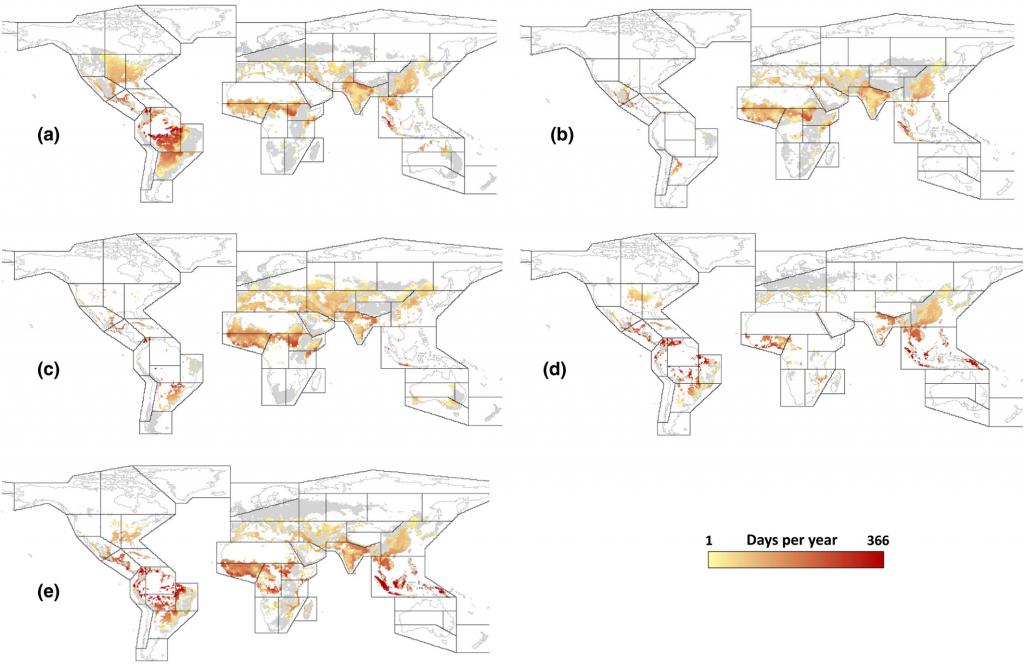

Figure 1. Change in the number of days per year above “extreme stress” values from 2000 to the 2090s for SSP5-8.5, estimated using the temperature humidity index (THI). Data mapped for each species’ current global distribution (Gilbert et al., 2018). Gray areas show no change from zero. Regional boundaries shown are for the IPCC subregions (Iturbide et al., 2020). (a) cattle, (b) goats, (c) sheep, (d) pigs, (e) poultry

Although our results are quite worrying, adaptation options exist that can help reduce the impacts of heat stress in smallholder systems. Some lower cost strategies include providing simple sheds and installing fans in sheds, animal baths and roof soaking.”

Philip Thornton, CCAFS Priorities and Policies for CSA Flagship Leader

In addition, exploiting existing variation in heat tolerance among different breeds and species may be a key adaptation strategy. Such shifts have been occurring already: from large ruminants to more heat-resilient goats for dairy production in Mediterranean systems, and from cattle to camels in pastoral systems in East Africa, for instance.

Higher input livestock production systems may need increasing investments in farm infrastructure if they are to adapt to increasing heat stress risk. There is a wide range of different ventilation systems, cooling systems, and building designs for confined and seasonally confined intensive livestock systems (pigs, poultry, beef, dairy) in temperate regions.

There is still a lot we don’t know about how increased heat stress will impact domesticated livestock populations and how it will affect production and productivity, especially for species other than cattle. We need to be able to provide context-specific, concrete recommendations to livestock keepers and policymakers that can help them adapt."

Philip Thornton, CCAFS Priorities and Policies for CSA Flagship Leader